Uxbridge Citizens for Clean Water

About

Uxbridge Citizens for Clean Water is an issue advocacy group working to increase understanding of the potential risks to public and private wells from dumping of unregulated soils across Central Massachusetts.

Key Issues

Press Release: We Cannot Let Central Massachusetts Become the Next Flint

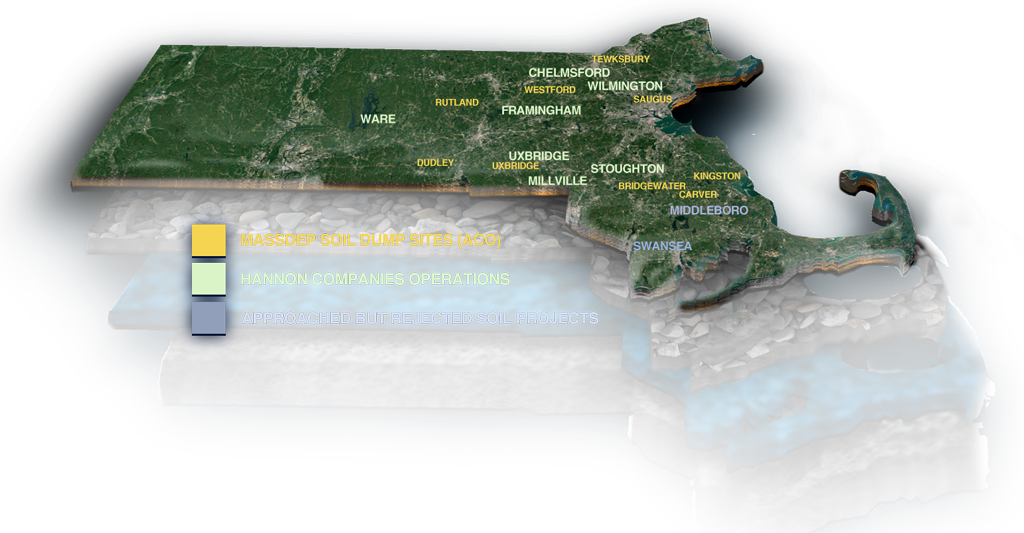

- In 2014 soil brokers began moving contaminated soil from large construction sites in Boston, and elsewhere, to small communities across Massachusetts, including Uxbridge. This followed a change in the law that allowed unregulated soils to be dumped almost anywhere, with only voluntary oversight from MassDEP at the project's discretion.

- Prior to 2014, these soils were limited to landfill capping and other tightly regulated projects. After 2014, the industry was allowed to self-regulate.

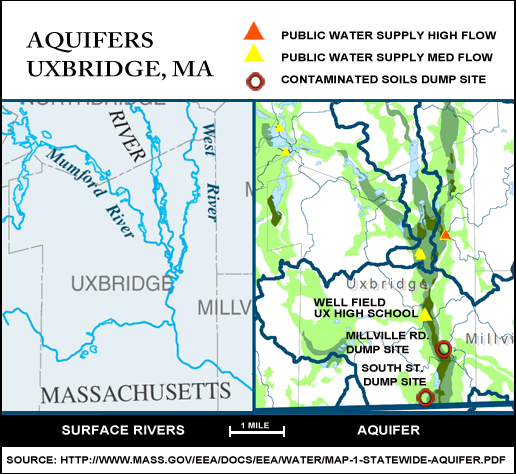

- In Uxbridge, the sites chosen for two dump sites are directly over a regionally vital aquifer. This area has a large population on private wells drawing from the Blackstone Aquifer.

- The companies and soil brokers operating in Uxbridge had a long line of non-compliance orders and court awards, often upaid, in the tens of millions of dollars. These types of projects have strong political connections on Beacon Hill and are supported with well-funded lobbying efforts.

- A local citizen's group began working to bring attention to the practices and was successful in passing local bylaws to protect the public interests of health, safety, and protection of vital resouces.

- Cease and desist orders were issued against the two projects in February 2017. One project locked its gates; the other continued to operate.

- In February 2018 a preliminary injunction was granted against the active site and soil importation ceased in Uxbridge.

- The Appeals court upheld the preliminary injunction and cases are continuing in Worcester Superior Court and the Land Court.

- UPDATE 2022: All five court cases reached final verdicts in favor of the Town of Uxbridge and established that municipalities have the duty and legal powers to regulate these projects.

- A contaminated well was documented by MassDEP across the street from one site. MassDEP is now testing 50 additional wells.

- UPDATE 2022: More than 200 wells were ultimately tested in the neighborhood across the street from the 775 Millville site. The eastern reaches of this neighborhood had prior contamination events due to an older "midnight dumping" event near Kempton Road. No tests have been undertaken on the properties, despite test wells being present. Where cancer causing chemicals, including TCE and PCE were found, MassDEP installed filtration systems. Some homeowners had to wait as long a seven months for the systems to be installed. There is no ongoing monitoring of the aquifer beneath the two dumping sites in Uxbridge.

- There are nine known sites with similar operations across the Commonwealth who have opted for voluntary oversight from MassDEP.

- There may be a large number of unregulated sites who did not notify MassDEP of their operations.

Legislative support is needed to:

- Establish protection zones for aquifers, especially in rural areas where private wells dominate.*

- Establish an industry-funded mitigation fund to provide clean water immediately after contamination events.

- Develop state and local bylaws to protect the public interest.

- Roll-back the 2014 legislation and require robust oversight and monitoring of soil dumping practices.

- Remove soils located near critical resources, including aquifers.

*Current water regulations are based on urban well-head protection zoning rules. That method fails to protect the public in areas where private wells are the main water supply, as is often the case in the Blackstone Region and Western Massachusetts.

Contaminated soil projects must be sited well away from all types of water supplies, including aquifers, municipal well-heads, and private wells.

After wells become contaminated, some Massachusetts families wait for up to a decade for clean water while the courts seek to assign liability. Most small communities cannot afford the high costs of extending municipal water to contaminated households without outside assistance. Massachusetts families in several communities have ended up relying bottled water for all household uses for many years.

Background and Timelines

- 2019 Conference: Pepperell Massachusetts

https://pepperell.vod.castus.tv/vod/?video=6b353f23-2c23-4aa0-8e0a-344912159314

Uxbridge talk begins at minute 25:00 - July 26, 2016 article

Potential conflict of interest vexes residents - April 22, 2017 article

Uxbridge conservation official in court in civil case - April 18, 2019 article

Uxbridge soil broker found guilty of fraud - May 19, 2022 court order

Bristol Superior Court 2173CV00684 PJ Keating Company vs Hannon, Patrick J et al: Acushnet case alleging interference with contractual relations will proceed - August 1, 2022 court order

Land Court 19 MISC 00081 (DRR) Town of Pepperell wins in Land Court to uphold its ban on commercial dumping grounds in face of a proposed soil reclamation project. The judge rules that the proposed 192,000 cubic yards of contaminated materials that the project proposed from 4.5 million tons of deliveries from four states could not be considered "de miminis" quantities as required by state law. - August 15, 2022 news coverage

NBC 10 I-Team at WJAR investigates court cases, fines and non-compliance orders against Patrick Hannon, currently serving as an environmental enforcement agent in the Town of Acushnet.

Court Actions of Note

Patrick Hannon and his companies face unpaid judgements in excess of $20 million with more than 70 filings on record.

- Suffolk Civil Superior Court

- Middlesex Superior Court

- Bristol Superior Court

- Worcester Superior Court

- U.S. Bankruptcy Court, Massachusetts

- 2016 - Bankruptcy denied for false statements

First Circuit - 2021 - Bankruptcy filing withdrawn after Mass DOR blocked it for unfiled tax returns.

- 2016 - Bankruptcy denied for false statements

- U.S. District Court, Massachusetts

Filing against 22 defendants in Uxbridge. Case dismissed in early motions following an Anti-SLAPP motion.

What's New?

Worcester Registry of Deeds

2020-2022

- "Sofia Gagua" attachment and settlement for court judgements for ABCD, King Root Capitol, and Spinazola judgements.

- "Patrick Hannon" certificate of judgement satisfied, ABCD, King Root Capitol, Spinazola judgements.

- "Sofia Gagua" payment of back taxes and liens, Town of Uxbridge,

- "Patriot Property Investments" attachment for judgement of fraudulent transfer and breach of contract with business partners at 775 Millville Road, Uxbridge project.

- "Patrick Hannon" Federal IRS judgement lien $7.9 million

Additional public filings are located in Norfolk Registry, Barnstable Registry, Suffolk Registry, Middlesex Registry, and in Maine.

June 17, 2021

January 6, 2019

May 24, 2018

February 22, 2018

February 9, 2018

February 6, 2018

On February 6, 2018, Associate Justice Elaine M. Buckley issued a preliminary injunction halting two operations moving soil to Uxbridge from sites including the Everett casino, Fan Pier, MBTA, and WRTA projects.

The dumping was taking place in farmland over the regionally vital Blackstone Valley Aquifer and could, potentially, put at risk private wells and water sources.

The sites' owners refused access multiple times to local and state inspectors.

Judge Buckley wrote, “The town has a valid interest in ensuring that the soil imported onto the property does not harm the citizens of the town and its ability to monitor that activity by requiring a permit is essential to protect its citizenry from the importation of contaminated soil and fill which would potentially leach into aquifers, wetlands causing permanent damage.”

How Did This Begin?

Boston's "Big Dig" project improved traffic flow through central Boston by moving major highways underground. In the course of the project, millions of tons of contaminated fill were trucked out of Boston.

Construction soils, laden with contaminates including lead, petroleum products, and heavy metals, were sent to landfills as capping material. As the landfills ran out of room the costs skyrocked and the locations willing to take the contaminated materials began to close.

With major construction on the horizon, a new scheme was quickly adopted in 2014. Led by the industry, legislation was designed to allow "unregulated" materials to be shipped to locations that were neither landfills nor hazardous waste sites.

The construction firms would be allowed to self-regulate.

Companies could enter into voluntary agreements with the Massachusetts' Department of Environmental Protection. Firms would be allowed to "sort" construction soils into categories and deposit RCS-1 and RCS-2 types in any location willing to take the material. The agreements were not required and materials not under MassDEP supervision would not be checked. The companies would hire their own, private, engineers to manage the soils.

Seeing the potential to collect millions in fees, soil brokers began looking for new sites. Within three years, at least nine large-scale operations opened for business across Massachusetts. One site proposed to accept 2.5 million tons of material and deposit it on a farm near the Blackstone Aquifer.

Projects, soils, and money, are on the move.

Press Releases

February 22, 2018

We Cannot Let Central Massachusetts Become the Next Flint

Aquifers

The Blackstone Valley Aquifer is a vibrant and vital resource to a multitude of communities in South Central Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Rural communities water supplies, unlike urban areas, are not directly protected by municipal well-head zoning methods. The majority of residents in an area can depend on private wells drawing on groundwater and shared aquifers for all their water.

If contaminates reach these aquifers, an entire region can lose its water supply.

Downloads

Preliminary Injunction

February 6, 2018

Associate Justice Elaine M. Buckley

Worcester Superior Court

Middleboro Soil Regulation

January 28, 2018

A complete file of supporting documents is available for qualified journalists to review.

Please contact us for a link.

We Cannot Let Central Massachusetts Become the Next Flint

UXBRIDGE, MA—In 2014, soil broker Patrick J. Hannon, began a project to dump more than 2.5 millions of tons of contaminated dirt over the high-yield Blackstone Valley Aquifer, which provides drinking water to much of south-central Massachusetts, and northern Rhode Island. Last week, Associate Justice Elaine M. Buckley ordered the operation stopped.

Uxbridge residents are asking how this began in a town that prohibits landfills. The site that was closed on February 6, 2018 was one of two large properties where cease-and-desist orders were issued over a year ago by the rural town.

One location, Rolling Hills, halted operations, as ordered by the town, in February 2017. The second, Green Acres, continued receiving up to 50 trucks per day until the Worcester Superior Court issued a preliminary injunction on February 6, 2018. Judge Buckley wrote, “The town has a valid interest in ensuring that the soil imported onto the property does not harm the citizens of the town and its ability to monitor that activity by requiring a permit is essential to protect its citizenry from the importation of contaminated soil and fill which would potentially leach into aquifers, wetlands causing permanent damage.”

Newspaper reports showed, the sites had refused inspections by local health and zoning officials. State officials were also blocked from the sites. Correspondence shows concerns were raised by local health officials to the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

State documents show, of the thousands of trucks that arrived, independent inspectors only sampled 10 vehicles over 17 months. Up to 60% failed even that minimal review. When a load failed inspection, it was returned. Other materials from the same work site were allowed to stay. While the project was required to have a full-time Licensed Site Professional (LSP), documents verify that loads had been checked by a non-LSP company employee and the contracted LSP engineering firm was not present when trucks arrived.

The receiving licensed engineer was required to perform “olfactory testing”, or a smell test, to determine if soil was safe. Another licensed engineer at the origin was supposed to test one sample every 500-650 cubic yards.

Documents show contaminated soils originated at some of Boston’s largest construction sites. Laboratory testing revealed numerous contaminates including lead, chromium, and petroleum products. Persistent problems with testing methods left enforcement officials unable to confirm the soils were compliant with standards.

A CHANGE IN THE LAW

Before 2014, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) allowed monitored landfills, operating with state permits and a mandatory 16-point criteria, to close and cap sites with contaminated fill.

The Central Artery “Big Dig” project moved enough material to give MassDEP some new headaches: the landfills were running out of room and prices were going up. With large building projects underway, and lobbying support from real-estate heavyweights, another scheme was devised and passed into law.

Private firms would sort their own soils, based on contamination levels. Soils designated RCS-1 and RCS-2 could be transported to communities outside of Boston and dumped in private, unlined gravel pits and farms. Private companies, paid by the developers and soil operators, would monitor the projects.

The projects were not required to notify MassDEP, but could sign voluntary agreements. Dumping sites did not need to be landfills. Owners did not have to get state permits, line the ground, or monitor the groundwater. There was no testing of local wells.

Public records show a history of political donations in the tens of millions from companies closely associated with the projects.Within three years, Massachusetts opened nine large-scale soil dumps under the scheme.

WHAT HAPPENED IN UXBRIDGE?

In Uxbridge, this created the perfect storm. Two private properties, one zoned for agriculture and one for residential use, attracted the attention of Patrick J. Hannon, a hauler whose companies face more than $20 million in court judgements and decades of non-compliance with MassDEP. Documents show cease-and desist orders, non-compliance orders and unfinished projects in Wilmington and Chelmsford that left landowners and communities with millions in legal liabilities and clean-up costs.

Two different Uxbridge property owners were approached by Mr. Hannon. Green Acres Reclamation opened on an historic farm owned by Eli Richardson, III. Rolling Hills operated on a property next to the Blackstone River owned by Immanuel, Corp. Mr. Hannon’s company, Agritech, and RHR, LLC., a firm run by his son, Patrick J. Hannon, Jr., managed both sites.

At the same time, Mr. Hannon obtained an appointment to the town’s Conservation Commission and became its chair. After numerous local complaints, one owner signed an Administrative Consent Order with MassDEP.

In the summer of 2017, a proposed fine of $19,500 was levied against the project as part of a non-compliance order by MassDEP. It is unclear if that fine was ever collected.

The other dump site, Rolling Hills, remained unmonitored for the life of the project.

Video at the 2016 Uxbridge Fall Annual Town Meeting shows Mr. Hannon saying,

“There’s a full time engineer there 8 hours a day, five days a week from Conoco engineering . . . Com 97-01 is a policy that allows soils to go to unlined landfills for grading and shaping for closure. I helped write the policy . . . There was a quarry that wanted to be filled in West Roxbury . . . I went to the quarry meetings and as a result of those quarry meetings HB 277 was written that requires a consent order.”

“I helped write that legislation for Senator Rush. Call him and ask him . . . These soils could be used at any playground, any daycare, anywhere . . .The [soil dump site at the ] quarry in Dudley is even closer to a Tier 2 waterway, which is also a surface water supply . . . “

“If you don’t have town water near your house, and that is a good portion of this town, everyone has a potentially productive drinking water supply area. That’s your aquifer. Your own private aquifer.” http://archive.uxbridgetv.org/Video/2445 : 1:31

While it may be unclear what Mr. Hannon intended by ‘private aquifers’, “potentially productive water supplies” is term generally used when designating potential municipal wellheads. In Uxbridge, as in much of the Blackstone Valley, the majority of of people use private wells, not municipal water. Locating potentially hazardous activities based on maps of municipal water supplies fails to protect the majority of local households. This region depends on the vitally important Blackstone Valley Aquifer.

Smaller communities, with few resources, can experience difficulties enforcing local laws against large, sophisticated operations. Local landowners may be at the mercy of soil operators who promise hefty profits.

Court records reveal large awards for damages and millions of dollars in potential liability from past projects. A case study of a previous project in Chelmsford identified $12.5 million in potential liability. Former business partners in Ware, Chelmsford, and Wilmington spent decades in court.

Allegations of misconduct at other soil operations appeared in an email Mr. Hannon wrote September 27, 2016 to George LaMonthe and that was copied to the MassDEP Commissioner, Martin Suuberg.

Hannon wrote, “Dudley is filing false weight tickets and accepting remediation waste, two of the five wells in Dudley were existing irrigation wells “not constructed to monitoring well standards, no installation logs for any of the wells.” Hannon continues, “The Dudley site is not just non compliant, it is engaging in criminal activities falsifying documents to conceal the true nature of the soils.” Hannon’s then observes, “I have been reviewing the Rutland files on the DEP file viewer, if you match the requirements of the ACO to what is actually done it is even worse than Dudley.”

Uxbridge passed monitoring provisions, a permit requirement, and fought in court for a year to enforce health and safety regulations. Other communities, after hearing of Uxbridge’s experience, including Middleboro, quickly passed local ordinances to prohibit these types of operations. Judge Buckley confirmed local communities have the duty and legal right to protect public resources, health, and safety.

As the Uxbridge projects face court enforcement, RHR, LLC., a firm run by Hannon’s son, Patrick J. Hannon, Jr. is actively advertising in municipal publications with promises of up to $60 million in payments to local governments. Mr. Hannon (Sr.). continues to operate under a variety of corporate entities, including Agritech.

Large corporations, including General Electric, are now asking the EPA for permission send Housatonic river dredgings, laden with PCBs, to local landfills rather than to out-of-state, licensed disposal facilities. A February 8, 2018 letter from Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ed Markey said GE estimates it could save the company $250 million.

Local communities rely on timely enforcement from MassDEP, an agency that has chronic staff shortages. Soil operations and large developers may have close associations with regulators over many projects. MassDEP’s enforcement role can conflict with its efforts to promote growth.

On June 14, 2006, the Mass. State Ethics Commission fined MassDEP employee Michael Rostkowski $10,000. Rostkowski was tasked with enforcing an Administrative Consent Order (ACO) at a Hannon landfill capping project in Wilmington. In February 2001, Rotskowski left MassDEP to work for Hannon on the same project he had supervised for the state, an ethics violation.

Hannon’s many companies have faced reviews, fines, and enforcement actions from various state agencies, including the Attorney General’s office and MassDEP. Documents show a history of failing pay prevailing wage to Big Dig transport drivers, non-compliance with a consent order in Chelmsford, and non-compliance with a consent order in Uxbridge, multiple cease-and-desist orders, and multiple court awards for failing to pay contractors and vendors. MassDEP has no authority to limit companies with similar histories from continuing to operate in Massachusetts.

Local governments are largely left to regulate the industry on their own. Communities, who often share large aquifers and regional water sources, have limited reach as they try to protect their residents. Contamination in one community can directly impact neighboring towns and cities.

All businesses have a legal duty to operate safely and not create a public nuisance. Judge Buckley agreed that an operation should never be allowed to put at risk any community’s precious resources, health, or safety.

We cannot depend on firms with clear conflicts of interest, multiple violations, and an ecosystem of perverse incentives to self-regulate. Projects must have robust supervision, fully-licensed managers, strong state supervision, and operate safely away from aquifers and other sensitive water resources, whether public or private. Operators, managers, and haulers must share liability with dumpsite owners.

Water is a shared resource that is vital to the life of every community. Action is needed now to protect all Massachusetts communities.

Our health and safety depend on it.

—

Supporting documents: Available by request to qualified journalists.

UPDATED 02/22/2018 Marlboro was corrected to Middleboro.